Last March, Bijoy Goswami and I sat down for a fascinating (and lengthy) conversation about mental models and bootstrapping at Progress Coffee on Austin's East Side (now Brew & Brew). The interview was recorded and transcribed. While preparing it for publication, Bijoy and I both felt it was important to stress that the chief mental model being explained here, that of the Maven-Relater-Evangelist, may or may not be useful to you in understanding your own place in the world. The point is not to take Bijoy's model, or anyone else's, and indiscriminately apply it to your own life. The point is rather to start thinking about how you might create models to better understand your own path.

- Sarah Vela

Bijoy, thanks so much for coming to speak with me today.

Absolutely, thank you.

I have a lot of questions for you. I would love to start off just by talking about mental models and what that means. What are mental models?

Mental models are something we do as humans so much, that we don't really realize we do it. The problem is that mental models inform everything we do. If you think about any activity that you might do as a human being, there's a mental model underneath it. Many folks have pointed the importance of mental models: Jean Piaget in education and Peter Senge in business, Darius Mahdjoubi here in town, to name a few. Wikipedia has a nice entry. Whether it's being a parent, or starting a business, or having a relationship, there's a mental model that you have about that issue, or that person, activity or or that entity.

I look at the process by which we come up with mental models: how do we articulate those mental models to each other and communicate them, and then where it goes wrong. For example, prejudice is basically a grooved-in mental model that has an incorrect view of reality. As humans we're constantly trying to make a model of reality through our brain that mediates everything that we do. To me, having better models is what we're about, to some extent. But because it's so natural and so ingrained, we don't think about the fact that that's what we're doing. My deal is to get people to build really good mental models for themselves, and to help them expose their own thought processes to themselves.

Give me an example of a mental model that you've created for yourself, and how did it help you?

The easiest one to start with is Maven, Relater, Evangelist, which I describe in my book The Human Fabric. MRE. Meals ready to eat (laughs). That model, number one, says that we're all different. So it takes the Golden Rule and turns it on its head. Yes, we're all human, but people have different energies and different locations on this triangle of energy: Maven, Relater, Evangelist. And where you're situated on that triangle influences your personality, the way you communicate, the way you relate, and so on and so forth. It's interesting because whenever I present the model to people they say, "But aren't I all three? I want to be all three!" People have a desire or built-in model that they should be all three, they should be good at all things, whatever those things are. The model is saying people have these different energies. We all do these activities. Just because the maven is living in thought space doesn't mean they take no actions. But it's the way that they take action that is important.

So, a model for people could be, "We're all the same," which is the Golden Rule. The Golden Rule pops out of a model that says people are all the same. And then you've got personality models all along the spectrum. If you march up the hill from one: "We're all the same," the most common mental model we use for "We're different" is men and women. We break up into two categories. Men are this way, women are that way. Clearly that's a fairly useful model, but it starts running out of steam pretty quickly, especially if you're trying to talk about our talents, our passions, and what we're doing. MRE is number three, it has three elements to it. Models like DISC have four. Enneagram has nine. And 16, Myers-Briggs, which is kind of the Microsoft, or the Google, of those (as in the 800 pound gorilla).

Again, the starting point is "Wait a second, people are not the same?" And "Oh yeah, I guess I see the world a certain way and I don't think about it." So number one is I've got to know myself. Because knowing yourself means you discover what you're good at and, perhaps more importantly, you discover what you're not good at.

So did creating that model help you to know where you fell in the model? Or did you already know.

I didn't know. And I didn't know the implications of it. Working on the model has helped me work out a number of things within and without myself. So, one of the big implications externally is that you seek out partners. Whatever activity you're doing, you seek out what I call a dance partner. I had been inadvertently finding dance partners in my life, but I hadn't realized the natural implication of this fact. I had inadvertently been developing what I call my Evangelist-Maven. So on this triangle I'm an Evangelist-Maven, I'm dominated by Evangelist energy, but my minor is Maven. And until then I didn't have a vocabulary for it. But it's interesting, back in high school I won the leadership and the academic awards...

Uh huh. So there you go.

There you go. It was already there, but no one said "Wow, you're a great evangelist, go work on that." I would take all these leadership roles, I would give lots of talks, do theater, those are all evangelist type of activities. Yet I was very studious. When I compared the two energies, really my Evangelist is my strong one. But not having the awareness that that was going on, or a model, I was just good at a lot of things.

It meant that I essentially spent a lot of time exploring avenues that weren't necessarily useful to explore. And if I knew that, I'd probably be more efficient about the way that I go went about it. So once I had a model for it, I could place myself in the model and realize I'm not supposed to do everything.

You were talking about dance partners earlier. I’m assuming those people were often relaters.

Or mavens. Yes, exactly. They were the complementary energy. Evangelists tended to be more of my friends, but we weren’t getting anything done because we were stepping all over each other. Whereas a maven or a relater, and more often mavens, because their strength was my minor, I could relate to them. But it wasn’t my deal, my core thing. One of my favorite examples is from high school. Our teacher, Miltinnie Yih, who was having us do Shakespeare creative projects. It was the morning it was due, and we’re waiting in front of the class for it to start, and I go, “I know, I’ll do a one-man King Lear.” So I’m writing it, I start Act I, I’m busily working on this thing, and my tall friend Jon Barden walks up to me, he says “hey, Bijoy.” And I’m like “yeah Jon,” kind of, can’t you see I’m busy?

Doing your one-man King Lear…

He goes, “what are you doing for your creative project?” I go, “I’m doing a one-man King Lear.” He goes, “wanna make it a two-man?” And I looked up and went, “Oh my god! Totally!” And we blew this thing out, it was the most hilarious project that I’d done, we ended up doing it at the theater in the school. The funny part was it was years later, and I did a short play called Mystic Cab, and then I turned it into a short film. Same thing. I decided to do a one-man, one act play. This was like five years ago. And I had been working on this thing and it was a total mess. I’m driving downtown and my friend Kert calls me and he says, “what are you doing?” I said, “I’m working on this thing, I signed up for FronteraFest at Hyde Park Theatre. I’m so screwed because five days from now I’m gonna have to present something, do 25 minutes of a play, and I’ve got nothing.” And he says, “I’ll do it with you.” And I said “oh my god, that would be so great.” And then I thought, why didn’t I think to ask him? Because he had some free time, he’s a theater guy. Right?

So now, have you learned? I mean now do you reach out?

Now, after 17 bonks on the head from the universe? (laughter). Yeah, I look at all my projects as collaborations now. And I think “who’s my dance partner, or dance partners?” within anything that I’m doing. The book I wrote was written with Dave Wolpert. The film I made was with Nils Juul-hansen. Bootstrap was one big collaboration. And I constantly go okay, my job is to reduce down into my thing and to create the space for others.

Now, one interesting caveat: I have a strong minor energy. Some people are very much on the points of the triangle. They’re like hard core mavens, hard core relater, hard core evangelist. Some of us are major-minors. We have a strong minor. Then we’ve got to reconcile within ourselves how those two integrate and don’t kill each other. I’ve had another journey, which is I was essentially outsourcing my maven to other people, and my internal maven was kind of pissed. Like, “hello dude, I’m here, I’m a maven.” And when the evangelist essentially took people off a cliff with my tech start-up, the maven said, “look, go in the corner, I’m gonna show you what’s up.” And in a sense these last number of years have been a maven exercise. My maven energy has been dominant in terms of building these models. And he showed my evangelist energy, “guess what, that’s my contribution. Yeah there’s these great mavens and relaters, and maybe even other evangelists that we want to partner with, but what you need to evangelize are these models. These are the creations that I’m coming up with, so now let’s work together.” So that’s another interesting self-reconciliation.

I find the choice of maven interesting, because I guess in my head there’s a little bit of a disconnect. I think of a maven as a proselytizer. But you think of a maven as a learner? or as a thinker?

An expert, yes.

An expert. Alright.

I mean these are just words, so you end up having to pick some word.

I’m just trying to understand the model a little bit better. And I think I do, but we have jumped so into it that I want to clarify it at this point. An evangelist is definitely your proselytizer, that’s definitely the person who is the leader, brings people together…

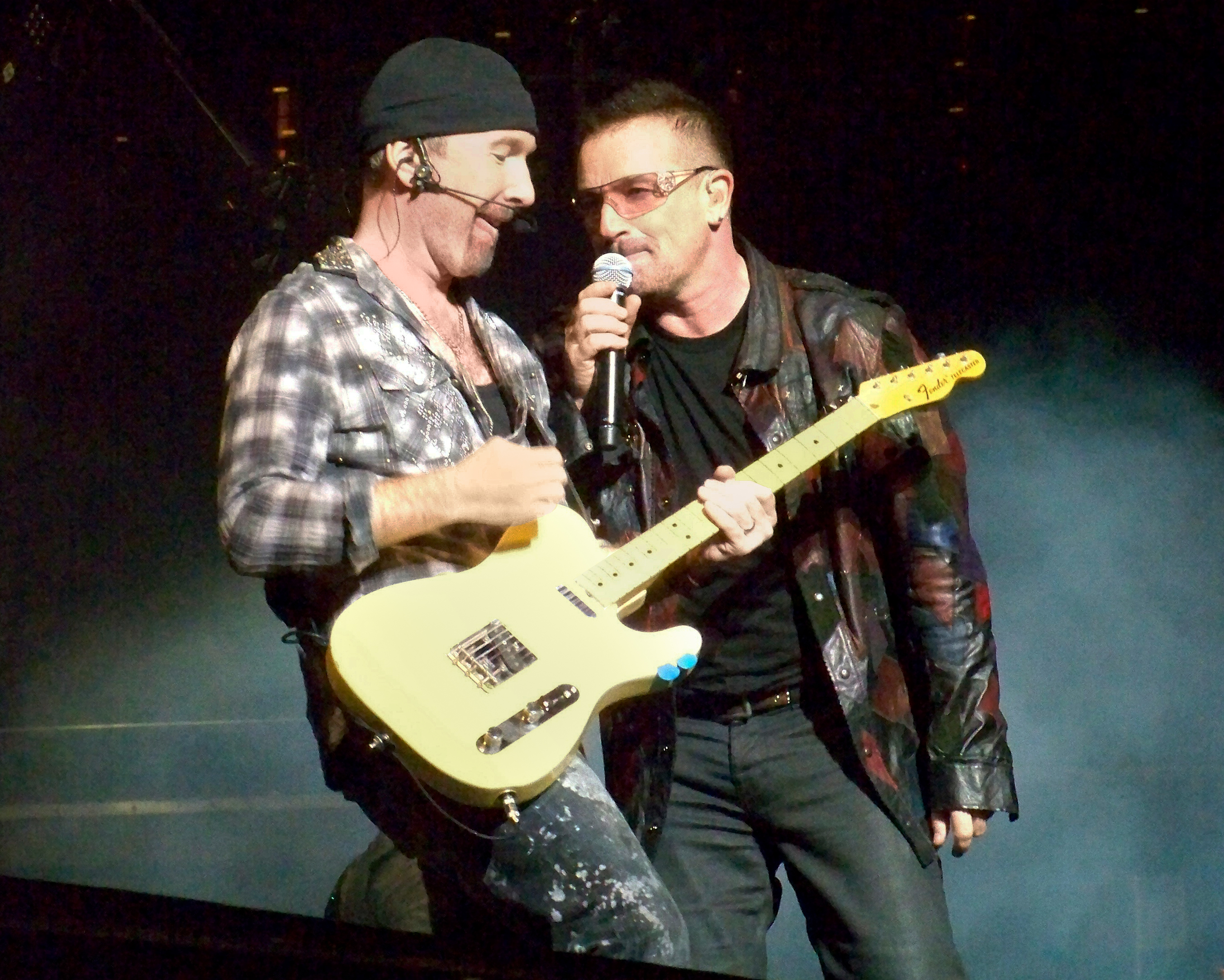

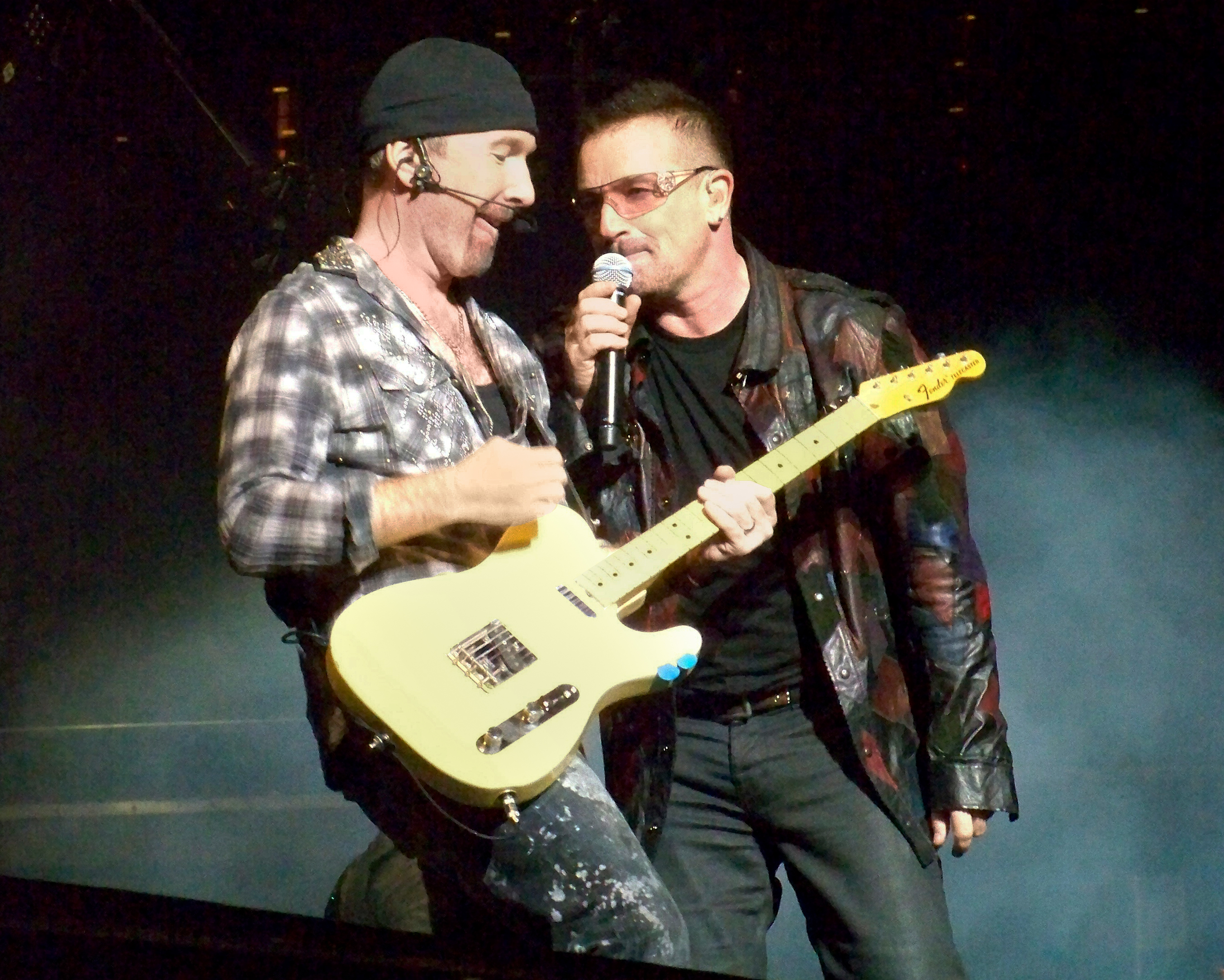

"Bono, not the Edge"

Bono, not The Edge. You know, The Edge is the maven, Bono is the evangelist. Steve Jobs, Steve Wozniak. You see these pairs.

And the relater? Where does the relater fit in? The relater feels like a third wheel to me, in your model. And that’s because you’re probably describing yourself that way.

That’s where I’m sitting, yeah. I live in that region of the world. The relater is the glue. The relater is, if we have The Human Fabric as the title of the book, the relater is the weaver of the human fabric. What they do is, mavens pick an area of the world and they study it. Relaters pick people. For relaters, people are the thing. And people are this infinite puzzle, and they’re just so interested in people. Oh my gosh, your journey, and how’s your day, and all this stuff. What they’re gathering data on is this entity called a person. And where they are. And then you should really talk to this person. My youngest brother is a total relater. and I have these great relaters in my world, and I look at what they do, and it’s incredible. It’s sometimes really frustrating, because as a maven or an evangelist you don’t think of a person as a universe unto themselves. but a relater does. So they’ll sit there and if you say, tell me about Joe, they’ll go oh, you know, and 20 minutes later you’ve got a soliloquy on Joe. And I’m like no, don’t tell me that much. What they’re doing, and this is the interesting thing, is I always used to draw the triangle as maven, evangelist, relater, like that…

Maven at the top.

Maven at the top. I didn’t know why. But I learned later that a model is already communicating information when you place the elements. So my friend Tina, who did the book cover, she has a company called Spoon Bend, it’s a graphic design marketing company. She took the triangle and she tipped it; and she also did three paintings that illustrated the energies of these three. She tipped it forward, and all of a sudden it all made sense. Because the evangelist was on the ground, pulling the triangle. the maven was stepping up on the top, and the relater was in the back, connecting, making sure everything is good, but taking a quiet role. That’s the thing with relaters is you can tell who the mavens are, you can tell who the evangelists are, the relaters are in the background - they’re the unseen third. But really each of these two resolves the duality for the other. So when the maven and the relater have a conflict, the evangelist can come in there and broker that discussion, because all of their energies are in a tight triangle like that. So, relaters are incredibly important.

Societies also fall into the triangle. Think of America: evangelist-maven. Right? I mean our dominant is we’re evangelists out here, we’re the Wild West, those are our heroes. Relaters don’t get much play here. Whereas in Japan, that’s a relater-maven culture. What’s Japan all about? It’s how you treat each other, how you interact. Whenever you’re looking for a culture’s energy, look at what they formalize. Germany: mavens. Uber-mavens.

You mentioned Hong Kong. Did you grow up in Hong Kong?

Yeah.

So how would you describe Hong Kong?

Hong Kong at night

Oh, evangelist. Very clearly. Which is interesting. Hong Kong and Singapore have an interesting relationship, because Singapore to me is maven, Hong Kong is very evangelist, and I always thought the obvious thing for them was to hook up and start, you know, getting all the business people in Hong Kong talking to the inventors and technologists in Singapore. That would be my economic prescription.

Tell me a little bit about Bootstrap Austin and your involvement with it.

I inadvertently stumbled into another model, which is bootstrapping. I would say bootstrap is the third way of entrepreneurship. So when we think about entrepreneurship, we think of it as one activity, and it’s not. It’s an infinite set of activities. I like to break things out into three. I think of the cookie cutter entrepreneurs, the funding-driven entrepreneurs, and the bootstrap entrepreneurs. Cookie cutters are anything from franchises to any business whose business model is already known. Doctors, lawyers…

Widget sellers…

Widget sellers. Someone else has already discovered the business model, and now you’re making one of your own, but you’re not making anything new. The new seems to always come from Silicon Valley, where you throw money at it, and you IPO it, and all that. But it turns out that bootstrapping is really the way that built-to-last companies get built. Microsoft, HP, Oracle, even Google…

So what is bootstrapping? What does that mean?

It means a lot of things. The simplest way I think of it as, from a business model point of view, is that the business model emerges from the process of bootstrapping.

And the process of bootstrapping is…

Is right action, right time. It’s demo, sell, build. It’s constraint creates innovation. It’s use everything. It’s most described by a story about Baron Munchausen. He supposedly found himself in a swamp. He’s drowning in the swamp, yelling for help, trying to get out of the swamp, no one’s there to help him. So he said well, I’m either going to be dead, or I’m able to get out. What am I going to do? I can’t get any help.

He looks around and sees his bootstraps, and pulls himself up by his bootstraps, and gets out of the swamp. There’s a competing myth which is that he pulled himself out by his hair, but "hairstrap" doesn’t quite roll off the tongue. So bootstrapping is that story. Wherever you are you can make progress. You can create something out of nothing. And what happens with people, is we often fall into “well, I don’t have what I need, I need to do this big thing so I need to go get resources from an external source.” That’s why Ir think of it as right action, right time. You are essentially letting something unfold and evolve and emerge, and you’re the shepherd of that emergence, you’re not the author and the controlling entrepreneur.

So it lends itself more to collaboration.

It does. It is fundamentally a co-creative process. You’re co-creating your ventures with your partners, with your customers, with the world. You’re on this journey of diminishing yourself into the right spot, and you’re watching what’s happening, and as you get better at watching, you make progress.

So we have this model, this map that we built, and it talks about the different elements that keep showing up. Each stage is nothing more than the birth of an element. So the “You” stage, the first stage, is the birth of you. What are your unique talents, what are your unique passions, what are you good at.

Once you start figuring that out, then you get into the “You plus You” (now called Quest(ion)) stage, where it’s like “Oh my gosh, do I want to go on this hero’s journey?” This is Joseph Campbell and all of that. Because many people are called, few take the action. That means that you’re going to go on this journey away from what society tells you that you’re supposed to do.

And if you say yes to that, then you enter into the “Ideation” phase. What are you going to do? That’s the birth of your “it.” Your product, your service, your experience, your cause, your community, whatever it is that you’re going to make. And then once you do that, you enter the Valley of Death. And then you’re on the hunt for this customer. You’re like, oh my gosh, someone please pay me for what I’m doing so I can be sustainable.

But all these elements keep going. The You still keeps going, the Inner Journey keeps going, the Product Journey keeps going, and the job of us as the entrepreneur is to weave them and integrate them together, so with the addition of a new element, kind of like a fugue, the addition of a new element doesn’t disrupt, but it forces and harmonizes with the previous elements.

I see this mental map as an animation. I mean, I imagine that it would be really useful to people. If mental mapping is about visualizing the process, or an idea, this is a particularly fluid process, as you describe it, as a fugue, as music. I wonder if you’ve ever thought about animating your mental maps.

I haven’t, but I’ve done some half-assed attempts in Power Point to show the elements coming in. But again I need my power of two on that.

Well I’m not the one to help you I’m afraid!

Thank you for illuminating a gap in my power of two (laughs). And not helping me at all.

You’re so welcome! As a relater maybe I can find somebody for you.

There you go.

Getting back to mental maps, or mental models. You say mental model, and a lot of other people say mind mapping, and I wonder if there’s a difference in your view about those two things.

Well, yeah. Mind Mapping is a very technical term where you essentially brainstorm by putting an idea in the center, and sort of spiking out. I remember when I discovered mind mapping in college. I was doing a research project in India, and I discovered mind mapping, and all of a sudden my world opened up, because it’s more mapped into the network structure of the brain. But a model is just a representation of reality. So a mind map could be a representation underneath that, but mind maps are subsets of all models.

Mind maps don’t work for me, and I think that has to do with how I learn. But I wonder if you run into this also with mental models. Are there people who absorb that information better and worse? Are there people who find this more or less useful? What is the response to mental models?

I think there’s a whole variety of responses. My models occupy the simple but not simplistic spot. My models are bootstrapping you into your mental models, if you like, to be sort of self-referential. Because I don’t want to give you the whole answer. What I find is mavens are the most dubious about my models, because I reduce them down.

I remember this art project that I did in 8th grade. I had a block to carve. And I started carving, and I had this elephant. My elephant was just this blocky thing, because I was afraid to cut too much, because you couldn’t glue it back on. That’s where I feel people are with mental models. And I’m always, like, cut, cut, cut down to the bone, so I can get to the essence. So when I say people fall into one of three categories, maven, relater, evangelist, both the mavens and the relaters go “noooo, that can’t be right.” Evangelists are like, “sweet, that’s easy, that’s quick, I need a quick model I can use,” so they’re good. Mavens are like, “that can’t be right. Really?” Because they look at people as mysterious.

And relaters like me say “but I’m all those things”

Exactly.

Because they relate.

Exactly. And “oh, people are so varied.” That’s where I get the resistance. Bootstrap, you get resistance from the other two sides. The cookie cutters go, “well, I want control over this, I’m not going to let it just go out.” And, “I need a business plan,” and stuff like that. And the funding-driven guys go, you know, “what are you talking about? I’m the master of the universe. I know what’s gonna happen, so why am i gonna let the process deliver?”

But you’re not creating the model for them.

Right.

So that’s okay.

It is, you’re right. That’s the subtlety of why I go slow with all this stuff, because I don’t want people to take my models and make them their reality. I want them to say, this is just showing up here. You asked about Bootstrap Austin. It started because I was even more convinced after my tech start-up deal, where I had raised half a million dollars from friends and family, spent it all, and found myself with nothing to show for it, going why didn’t I trust myself? I’m a bootstrapper, I knew about bootstrapping. I didn’t know the whole model. But I started with it back at Stanford.

I knew that was my path, not the Silicon Valley dominant path. What’s the founding company of Stanford? HP. Bootstrap. Scott Cook came and spoke, the founder of Quicken. Bootstrap. Oracle: bootstrap. And yet I had allowed myself to go away from my own intuition. So I was talking to a lot of entrepreneurs, and they wanted to get funding. This was 2002, 2003. And I said “dude, you want to bootstrap your company. You want control,” and so on and so forth. I was having all these lunches, coffees, and dinners, and it started to get to be a real pain. So I thought, I’ll get these people together, I’ll introduce them to each other, and that’s how Bootstrap Austin was born.

Bijoy, thanks for your time today, and good luck with SXSW and your upcoming projects!

Bijoy's Amazon list of suggested reading material can be found here.

Paintings by Tina Schweiger.

- Sarah Vela

About Bijoy:

Bijoy Goswami was born in Bangalore, India on April 15, 1973, to a Catholic mother and a Hindu father. They moved to Taiwan when he was ten, and Hong Kong when he was fourteen. He came to the U.S. in 1991 to attend Stanford, where he studied Computer Science, Economics, History and inter-disciplinary honors in Science, Technology and Society (STS). He moved to Austin in 1995 to join a software startup. In April, 2000 he co-founded a software company with his friend Bruce Krysiak. In 2003 he began his true work as a model-builder and evangelist.Bijoy, thanks so much for coming to speak with me today.

Absolutely, thank you.

I have a lot of questions for you. I would love to start off just by talking about mental models and what that means. What are mental models?

Mental models are something we do as humans so much, that we don't really realize we do it. The problem is that mental models inform everything we do. If you think about any activity that you might do as a human being, there's a mental model underneath it. Many folks have pointed the importance of mental models: Jean Piaget in education and Peter Senge in business, Darius Mahdjoubi here in town, to name a few. Wikipedia has a nice entry. Whether it's being a parent, or starting a business, or having a relationship, there's a mental model that you have about that issue, or that person, activity or or that entity.

I look at the process by which we come up with mental models: how do we articulate those mental models to each other and communicate them, and then where it goes wrong. For example, prejudice is basically a grooved-in mental model that has an incorrect view of reality. As humans we're constantly trying to make a model of reality through our brain that mediates everything that we do. To me, having better models is what we're about, to some extent. But because it's so natural and so ingrained, we don't think about the fact that that's what we're doing. My deal is to get people to build really good mental models for themselves, and to help them expose their own thought processes to themselves.

Give me an example of a mental model that you've created for yourself, and how did it help you?

The easiest one to start with is Maven, Relater, Evangelist, which I describe in my book The Human Fabric. MRE. Meals ready to eat (laughs). That model, number one, says that we're all different. So it takes the Golden Rule and turns it on its head. Yes, we're all human, but people have different energies and different locations on this triangle of energy: Maven, Relater, Evangelist. And where you're situated on that triangle influences your personality, the way you communicate, the way you relate, and so on and so forth. It's interesting because whenever I present the model to people they say, "But aren't I all three? I want to be all three!" People have a desire or built-in model that they should be all three, they should be good at all things, whatever those things are. The model is saying people have these different energies. We all do these activities. Just because the maven is living in thought space doesn't mean they take no actions. But it's the way that they take action that is important.

So, a model for people could be, "We're all the same," which is the Golden Rule. The Golden Rule pops out of a model that says people are all the same. And then you've got personality models all along the spectrum. If you march up the hill from one: "We're all the same," the most common mental model we use for "We're different" is men and women. We break up into two categories. Men are this way, women are that way. Clearly that's a fairly useful model, but it starts running out of steam pretty quickly, especially if you're trying to talk about our talents, our passions, and what we're doing. MRE is number three, it has three elements to it. Models like DISC have four. Enneagram has nine. And 16, Myers-Briggs, which is kind of the Microsoft, or the Google, of those (as in the 800 pound gorilla).

Again, the starting point is "Wait a second, people are not the same?" And "Oh yeah, I guess I see the world a certain way and I don't think about it." So number one is I've got to know myself. Because knowing yourself means you discover what you're good at and, perhaps more importantly, you discover what you're not good at.

So did creating that model help you to know where you fell in the model? Or did you already know.

I didn't know. And I didn't know the implications of it. Working on the model has helped me work out a number of things within and without myself. So, one of the big implications externally is that you seek out partners. Whatever activity you're doing, you seek out what I call a dance partner. I had been inadvertently finding dance partners in my life, but I hadn't realized the natural implication of this fact. I had inadvertently been developing what I call my Evangelist-Maven. So on this triangle I'm an Evangelist-Maven, I'm dominated by Evangelist energy, but my minor is Maven. And until then I didn't have a vocabulary for it. But it's interesting, back in high school I won the leadership and the academic awards...

Uh huh. So there you go.

There you go. It was already there, but no one said "Wow, you're a great evangelist, go work on that." I would take all these leadership roles, I would give lots of talks, do theater, those are all evangelist type of activities. Yet I was very studious. When I compared the two energies, really my Evangelist is my strong one. But not having the awareness that that was going on, or a model, I was just good at a lot of things.

It meant that I essentially spent a lot of time exploring avenues that weren't necessarily useful to explore. And if I knew that, I'd probably be more efficient about the way that I go went about it. So once I had a model for it, I could place myself in the model and realize I'm not supposed to do everything.

You were talking about dance partners earlier. I’m assuming those people were often relaters.

Or mavens. Yes, exactly. They were the complementary energy. Evangelists tended to be more of my friends, but we weren’t getting anything done because we were stepping all over each other. Whereas a maven or a relater, and more often mavens, because their strength was my minor, I could relate to them. But it wasn’t my deal, my core thing. One of my favorite examples is from high school. Our teacher, Miltinnie Yih, who was having us do Shakespeare creative projects. It was the morning it was due, and we’re waiting in front of the class for it to start, and I go, “I know, I’ll do a one-man King Lear.” So I’m writing it, I start Act I, I’m busily working on this thing, and my tall friend Jon Barden walks up to me, he says “hey, Bijoy.” And I’m like “yeah Jon,” kind of, can’t you see I’m busy?

Doing your one-man King Lear…

He goes, “what are you doing for your creative project?” I go, “I’m doing a one-man King Lear.” He goes, “wanna make it a two-man?” And I looked up and went, “Oh my god! Totally!” And we blew this thing out, it was the most hilarious project that I’d done, we ended up doing it at the theater in the school. The funny part was it was years later, and I did a short play called Mystic Cab, and then I turned it into a short film. Same thing. I decided to do a one-man, one act play. This was like five years ago. And I had been working on this thing and it was a total mess. I’m driving downtown and my friend Kert calls me and he says, “what are you doing?” I said, “I’m working on this thing, I signed up for FronteraFest at Hyde Park Theatre. I’m so screwed because five days from now I’m gonna have to present something, do 25 minutes of a play, and I’ve got nothing.” And he says, “I’ll do it with you.” And I said “oh my god, that would be so great.” And then I thought, why didn’t I think to ask him? Because he had some free time, he’s a theater guy. Right?

So now, have you learned? I mean now do you reach out?

Now, after 17 bonks on the head from the universe? (laughter). Yeah, I look at all my projects as collaborations now. And I think “who’s my dance partner, or dance partners?” within anything that I’m doing. The book I wrote was written with Dave Wolpert. The film I made was with Nils Juul-hansen. Bootstrap was one big collaboration. And I constantly go okay, my job is to reduce down into my thing and to create the space for others.

Now, one interesting caveat: I have a strong minor energy. Some people are very much on the points of the triangle. They’re like hard core mavens, hard core relater, hard core evangelist. Some of us are major-minors. We have a strong minor. Then we’ve got to reconcile within ourselves how those two integrate and don’t kill each other. I’ve had another journey, which is I was essentially outsourcing my maven to other people, and my internal maven was kind of pissed. Like, “hello dude, I’m here, I’m a maven.” And when the evangelist essentially took people off a cliff with my tech start-up, the maven said, “look, go in the corner, I’m gonna show you what’s up.” And in a sense these last number of years have been a maven exercise. My maven energy has been dominant in terms of building these models. And he showed my evangelist energy, “guess what, that’s my contribution. Yeah there’s these great mavens and relaters, and maybe even other evangelists that we want to partner with, but what you need to evangelize are these models. These are the creations that I’m coming up with, so now let’s work together.” So that’s another interesting self-reconciliation.

I find the choice of maven interesting, because I guess in my head there’s a little bit of a disconnect. I think of a maven as a proselytizer. But you think of a maven as a learner? or as a thinker?

An expert, yes.

An expert. Alright.

I mean these are just words, so you end up having to pick some word.

I’m just trying to understand the model a little bit better. And I think I do, but we have jumped so into it that I want to clarify it at this point. An evangelist is definitely your proselytizer, that’s definitely the person who is the leader, brings people together…

"Bono, not the Edge"

Bono, not The Edge. You know, The Edge is the maven, Bono is the evangelist. Steve Jobs, Steve Wozniak. You see these pairs.

And the relater? Where does the relater fit in? The relater feels like a third wheel to me, in your model. And that’s because you’re probably describing yourself that way.

That’s where I’m sitting, yeah. I live in that region of the world. The relater is the glue. The relater is, if we have The Human Fabric as the title of the book, the relater is the weaver of the human fabric. What they do is, mavens pick an area of the world and they study it. Relaters pick people. For relaters, people are the thing. And people are this infinite puzzle, and they’re just so interested in people. Oh my gosh, your journey, and how’s your day, and all this stuff. What they’re gathering data on is this entity called a person. And where they are. And then you should really talk to this person. My youngest brother is a total relater. and I have these great relaters in my world, and I look at what they do, and it’s incredible. It’s sometimes really frustrating, because as a maven or an evangelist you don’t think of a person as a universe unto themselves. but a relater does. So they’ll sit there and if you say, tell me about Joe, they’ll go oh, you know, and 20 minutes later you’ve got a soliloquy on Joe. And I’m like no, don’t tell me that much. What they’re doing, and this is the interesting thing, is I always used to draw the triangle as maven, evangelist, relater, like that…

Maven at the top.

Maven at the top. I didn’t know why. But I learned later that a model is already communicating information when you place the elements. So my friend Tina, who did the book cover, she has a company called Spoon Bend, it’s a graphic design marketing company. She took the triangle and she tipped it; and she also did three paintings that illustrated the energies of these three. She tipped it forward, and all of a sudden it all made sense. Because the evangelist was on the ground, pulling the triangle. the maven was stepping up on the top, and the relater was in the back, connecting, making sure everything is good, but taking a quiet role. That’s the thing with relaters is you can tell who the mavens are, you can tell who the evangelists are, the relaters are in the background - they’re the unseen third. But really each of these two resolves the duality for the other. So when the maven and the relater have a conflict, the evangelist can come in there and broker that discussion, because all of their energies are in a tight triangle like that. So, relaters are incredibly important.

Societies also fall into the triangle. Think of America: evangelist-maven. Right? I mean our dominant is we’re evangelists out here, we’re the Wild West, those are our heroes. Relaters don’t get much play here. Whereas in Japan, that’s a relater-maven culture. What’s Japan all about? It’s how you treat each other, how you interact. Whenever you’re looking for a culture’s energy, look at what they formalize. Germany: mavens. Uber-mavens.

You mentioned Hong Kong. Did you grow up in Hong Kong?

Yeah.

So how would you describe Hong Kong?

Hong Kong at night

Oh, evangelist. Very clearly. Which is interesting. Hong Kong and Singapore have an interesting relationship, because Singapore to me is maven, Hong Kong is very evangelist, and I always thought the obvious thing for them was to hook up and start, you know, getting all the business people in Hong Kong talking to the inventors and technologists in Singapore. That would be my economic prescription.

Tell me a little bit about Bootstrap Austin and your involvement with it.

I inadvertently stumbled into another model, which is bootstrapping. I would say bootstrap is the third way of entrepreneurship. So when we think about entrepreneurship, we think of it as one activity, and it’s not. It’s an infinite set of activities. I like to break things out into three. I think of the cookie cutter entrepreneurs, the funding-driven entrepreneurs, and the bootstrap entrepreneurs. Cookie cutters are anything from franchises to any business whose business model is already known. Doctors, lawyers…

Widget sellers…

Widget sellers. Someone else has already discovered the business model, and now you’re making one of your own, but you’re not making anything new. The new seems to always come from Silicon Valley, where you throw money at it, and you IPO it, and all that. But it turns out that bootstrapping is really the way that built-to-last companies get built. Microsoft, HP, Oracle, even Google…

So what is bootstrapping? What does that mean?

It means a lot of things. The simplest way I think of it as, from a business model point of view, is that the business model emerges from the process of bootstrapping.

And the process of bootstrapping is…

Is right action, right time. It’s demo, sell, build. It’s constraint creates innovation. It’s use everything. It’s most described by a story about Baron Munchausen. He supposedly found himself in a swamp. He’s drowning in the swamp, yelling for help, trying to get out of the swamp, no one’s there to help him. So he said well, I’m either going to be dead, or I’m able to get out. What am I going to do? I can’t get any help.

Baron Munchausen

He looks around and sees his bootstraps, and pulls himself up by his bootstraps, and gets out of the swamp. There’s a competing myth which is that he pulled himself out by his hair, but "hairstrap" doesn’t quite roll off the tongue. So bootstrapping is that story. Wherever you are you can make progress. You can create something out of nothing. And what happens with people, is we often fall into “well, I don’t have what I need, I need to do this big thing so I need to go get resources from an external source.” That’s why Ir think of it as right action, right time. You are essentially letting something unfold and evolve and emerge, and you’re the shepherd of that emergence, you’re not the author and the controlling entrepreneur.

So it lends itself more to collaboration.

It does. It is fundamentally a co-creative process. You’re co-creating your ventures with your partners, with your customers, with the world. You’re on this journey of diminishing yourself into the right spot, and you’re watching what’s happening, and as you get better at watching, you make progress.

So we have this model, this map that we built, and it talks about the different elements that keep showing up. Each stage is nothing more than the birth of an element. So the “You” stage, the first stage, is the birth of you. What are your unique talents, what are your unique passions, what are you good at.

Once you start figuring that out, then you get into the “You plus You” (now called Quest(ion)) stage, where it’s like “Oh my gosh, do I want to go on this hero’s journey?” This is Joseph Campbell and all of that. Because many people are called, few take the action. That means that you’re going to go on this journey away from what society tells you that you’re supposed to do.

And if you say yes to that, then you enter into the “Ideation” phase. What are you going to do? That’s the birth of your “it.” Your product, your service, your experience, your cause, your community, whatever it is that you’re going to make. And then once you do that, you enter the Valley of Death. And then you’re on the hunt for this customer. You’re like, oh my gosh, someone please pay me for what I’m doing so I can be sustainable.

The Hero's Journey

But all these elements keep going. The You still keeps going, the Inner Journey keeps going, the Product Journey keeps going, and the job of us as the entrepreneur is to weave them and integrate them together, so with the addition of a new element, kind of like a fugue, the addition of a new element doesn’t disrupt, but it forces and harmonizes with the previous elements.

I see this mental map as an animation. I mean, I imagine that it would be really useful to people. If mental mapping is about visualizing the process, or an idea, this is a particularly fluid process, as you describe it, as a fugue, as music. I wonder if you’ve ever thought about animating your mental maps.

I haven’t, but I’ve done some half-assed attempts in Power Point to show the elements coming in. But again I need my power of two on that.

Well I’m not the one to help you I’m afraid!

Thank you for illuminating a gap in my power of two (laughs). And not helping me at all.

You’re so welcome! As a relater maybe I can find somebody for you.

There you go.

Getting back to mental maps, or mental models. You say mental model, and a lot of other people say mind mapping, and I wonder if there’s a difference in your view about those two things.

Well, yeah. Mind Mapping is a very technical term where you essentially brainstorm by putting an idea in the center, and sort of spiking out. I remember when I discovered mind mapping in college. I was doing a research project in India, and I discovered mind mapping, and all of a sudden my world opened up, because it’s more mapped into the network structure of the brain. But a model is just a representation of reality. So a mind map could be a representation underneath that, but mind maps are subsets of all models.

Mind maps don’t work for me, and I think that has to do with how I learn. But I wonder if you run into this also with mental models. Are there people who absorb that information better and worse? Are there people who find this more or less useful? What is the response to mental models?

I think there’s a whole variety of responses. My models occupy the simple but not simplistic spot. My models are bootstrapping you into your mental models, if you like, to be sort of self-referential. Because I don’t want to give you the whole answer. What I find is mavens are the most dubious about my models, because I reduce them down.

I remember this art project that I did in 8th grade. I had a block to carve. And I started carving, and I had this elephant. My elephant was just this blocky thing, because I was afraid to cut too much, because you couldn’t glue it back on. That’s where I feel people are with mental models. And I’m always, like, cut, cut, cut down to the bone, so I can get to the essence. So when I say people fall into one of three categories, maven, relater, evangelist, both the mavens and the relaters go “noooo, that can’t be right.” Evangelists are like, “sweet, that’s easy, that’s quick, I need a quick model I can use,” so they’re good. Mavens are like, “that can’t be right. Really?” Because they look at people as mysterious.

And relaters like me say “but I’m all those things”

Exactly.

Because they relate.

Exactly. And “oh, people are so varied.” That’s where I get the resistance. Bootstrap, you get resistance from the other two sides. The cookie cutters go, “well, I want control over this, I’m not going to let it just go out.” And, “I need a business plan,” and stuff like that. And the funding-driven guys go, you know, “what are you talking about? I’m the master of the universe. I know what’s gonna happen, so why am i gonna let the process deliver?”

But you’re not creating the model for them.

Right.

So that’s okay.

It is, you’re right. That’s the subtlety of why I go slow with all this stuff, because I don’t want people to take my models and make them their reality. I want them to say, this is just showing up here. You asked about Bootstrap Austin. It started because I was even more convinced after my tech start-up deal, where I had raised half a million dollars from friends and family, spent it all, and found myself with nothing to show for it, going why didn’t I trust myself? I’m a bootstrapper, I knew about bootstrapping. I didn’t know the whole model. But I started with it back at Stanford.

I knew that was my path, not the Silicon Valley dominant path. What’s the founding company of Stanford? HP. Bootstrap. Scott Cook came and spoke, the founder of Quicken. Bootstrap. Oracle: bootstrap. And yet I had allowed myself to go away from my own intuition. So I was talking to a lot of entrepreneurs, and they wanted to get funding. This was 2002, 2003. And I said “dude, you want to bootstrap your company. You want control,” and so on and so forth. I was having all these lunches, coffees, and dinners, and it started to get to be a real pain. So I thought, I’ll get these people together, I’ll introduce them to each other, and that’s how Bootstrap Austin was born.

Bijoy, thanks for your time today, and good luck with SXSW and your upcoming projects!

Bijoy's Amazon list of suggested reading material can be found here.

Paintings by Tina Schweiger.

No comments:

Post a Comment